- Home

- Features

- Business

- Active

- Sports

- Shop

Top Insights

How Financial Surveillance Threatens Our Democracies: Part 2

Undemonstrated Effectiveness and Efficiency

I’m not aware of any study establishing the effectiveness of KYC measures in combating money laundering. And it’s not for lack of searching.

Conversely, there are numerous studies tending to conclude the opposite. Ronald Pol, a researcher at La Trobe University in Melbourne, synthesized in a research paper published in 2020, many works: Anand 2011; Brzoska 2016; Chaikin 2009; Ferwerda 2009; Findley, Nielson, and Sharman 2014; Harvey 2008; Levi 2002, 2012; Levi and Maguire 2004; Levi and Reuter 2006, 2009; Naylor 2005; Pol 2018b; Reuter and Truman 2004; Rider 2002a, 2002b, 2004; Sharman 2011; van Duyne 2003, 2011; Verhage 2017.

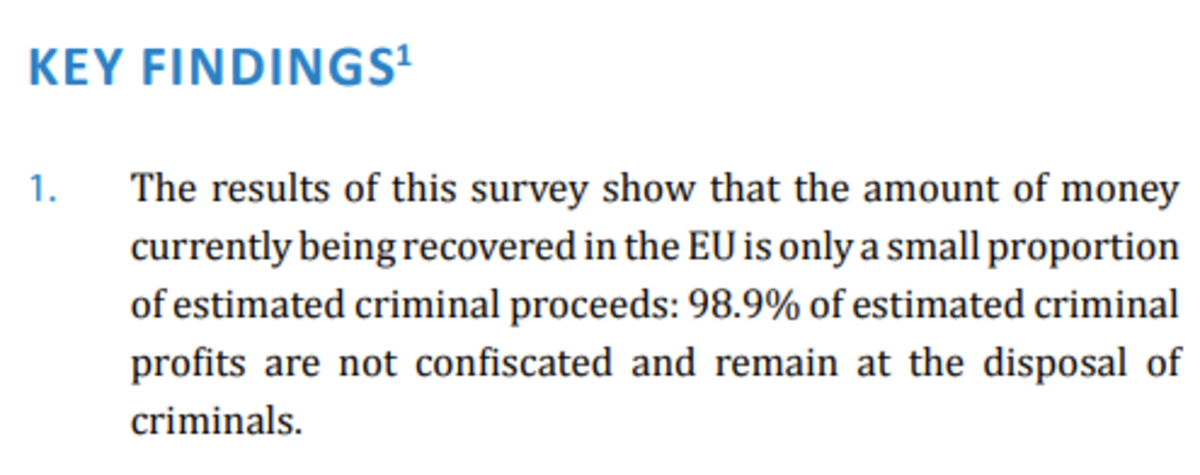

The main finding of this research paper is captured in a more than eloquent title: “Money Laundering Control: The Least Effective Public Policy in the World?”

What do we learn?

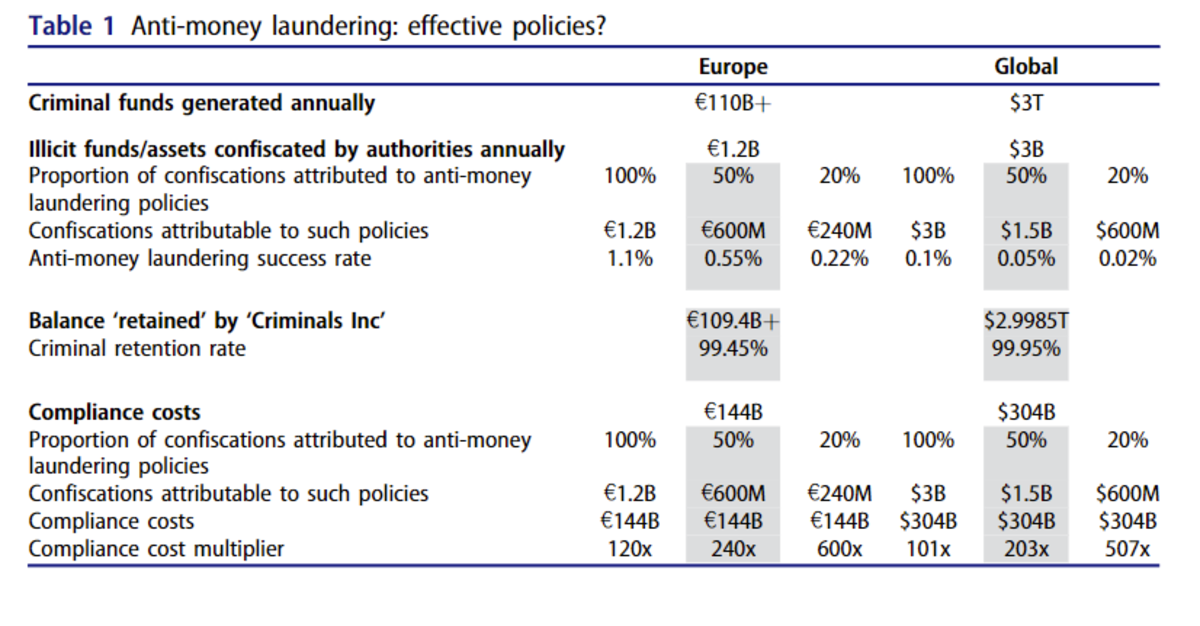

That KYC and AML procedures allow the recovery of approximately 0.05% of global criminal money, meaning $1.5 billion out of the $3 trillion in crime money circulating worldwide each year. And this is assuming that 50% of the recovered money is through these procedures, whereas an empirical study in New Zealand showed a different reality, where 80% of seizures were made through conventional means, and only 20% through KYC and AML procedures.

The author of the paper summarizes it as follows: “if the impact of three decades of money laundering controls barely registers as a rounding error in criminal accounts and “Criminals, Inc” keep up to 99.95 percent of the earnings from misery, and reasonable prospects for better outcomes remain persistently unexplored, the harsh reality is that the current policy prescription inadvertently protects, supports and enables much of the serious profit-motivated crime that it seeks to counter. In any event, the anti-money laundering experiment remains a viable candidate for the title of least effective policy initiative, ever, anywhere (Cassara 2017, 2).”

A Europol study in 201636 yields similar figures: criminals would retain nearly 99% of their profits.

That’s effectiveness covered.

What about efficiency, meaning what resources are mobilized to achieve this result?

The answer is once again confusing.

Studies vary widely in estimating the compliance costs imposed on businesses, particularly financial ones, ranging in 2018 from $304 billion annually according to LexisNexis, to $1.28 trillion according to Thomson Reuters37, without even considering the costs imposed on states and public services, as well as indirect costs (productivity losses, frictions, etc.).

Even by a low estimate, for every euro extracted from crime, 200€ were spent. The situation is so absurd in Europe that compliance costs (€144 billion) exceed the total money (€110 billion) generated by crime each year!

Faced with such poor results and the magnitude of their costs, any sensible person or company would take some time to reflect on the sustainability of such a system. But we are dealing with a religion here, and asking for evidence and reasoning can make one suspect of complicity with money laundering and terrorism.

This industry has also become extremely lucrative for a range of actors who have developed a wide range of services: compliance-specialized lawyers, consulting firms, as well as startups offering dedicated tools, even named RegTech. Interestingly enough, with nearly $4.3 billion in penalties imposed on financial institutions in 2018, and $8.1 billion in 2019, the business also proves lucrative for states, which earn more in fines than they recover from criminals…

Totalitarian regimes dreamed of it, liberal democracies did it: financial surveillance and its consequences

With the imposition of these procedures on the financial system, new or existing risks take on major proportions.

The first is censorship, linked to the drastic reduction of online anonymity. The second is arbitrariness in the application of decisions and sanctions. The third is the theft of sensitive information.

Financial censorship as a political weapon for democratic asphyxiation

The risk of censorship is often perceived as a distant problem in Western democracies. And yet, living in a democracy does not prevent the temptation of censorship that prevails in human beings, and examples abound.

The Democracy Index published by the British newspaper The Economist ranks Canada 13th, the United Kingdom 18th, South Korea 22nd. All are classified as “full democracies,” ahead of France (23rd). India, the world’s largest democracy, ranks 41st, not far from our Belgian (36th) or Italian (34th) neighbors.

And yet, these countries have a story to tell about censorship related to customer knowledge procedures and KYC.

In Canada, for example, as recently as 2022, as truckers’ protests intensified, the Ontario government and then the Canadian government declared a state of emergency and imposed financial coercion measures on the protest movement, bypassing the usual democratic and legal processes. It was the first time in Canadian history that such a state of emergency was imposed.

Under the pretext of wanting to know the origin of the funds financing the crowdfunding campaigns supporting the movement, the financial surveillance agency (FINTRAC) was involved. The two financial platforms GoFundMe and GiveSendGo were forced to freeze the funds. Even more worrying, the Canadian government invoked its emergency powers to freeze the individual accounts of nearly a hundred people involved in the protests. A real financial suffocation under a political pretext.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the reasons behind the protests is besides the point. This state of emergency would later be deemed unconstitutional by the Federal Court of Canada in January 202438. But the damage is done: the protest has ceased, protesters have been financially choked, the rule of law and individual freedoms have been diminished.

In the United Kingdom, another case made headlines and caused quite a scandal: that of Nigel Farage. This Brexit supporter and leader, a client of the same bank for 43 years, announced in 2023 on Twitter39 that his accounts had been closed without explanation. Two days later, as the scandal erupted in the UK, he announced that his requests to open accounts had been rejected by 9 banks, under the pretext that he is a “politically exposed person,” a PEP, an acronym created by these customer knowledge regulations. However, other political decision-makers do not face the same problems in opening or maintaining bank accounts, raising questions about differential treatment based on political opinions.

The incident caused a stir in the UK, and the BBC confirmed that the account had been closed for political reasons40. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak had to address the issue41 and summoned the country’s major banks to ensure their respect of freedom of expression.

Even more recently in India, at the end of March 2024, the influence of the banking sector on the finances of economic actors was materialized into the country’s politics, enabling the ruling party to financially suffocate its rival, the Indian National Congress, the former party of Gandhi.

As the Human Rights Foundation recalls in its 17th Financial Freedom Report newsletter42, “The Indian government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, froze the bank accounts of its largest political opposition party, the Indian National Congress (INC), citing allegations of tax evasion, just weeks before the upcoming election. According to INC statements on X43, ‘all our bank accounts have been frozen. We cannot carry out our campaign work. We cannot support our workers and candidates. Our leaders cannot travel across the country.’ A few days later, the Indian agency for fighting financial crime also arrested opposition leader Arvind Kejriwal44 in what is seen as a broader move to eliminate competition in the upcoming elections. These events highlight the growing need for a neutral and apolitical currency as a tool of democratic activism and for political campaigns.”

It is tempting to think that such things “do not happen here.” But the examples I have deliberately cited are democracies, most of which are better ranked in this regard than France.

And France has already shifted on similar issues.

An unfair system : selective enforcement of measures

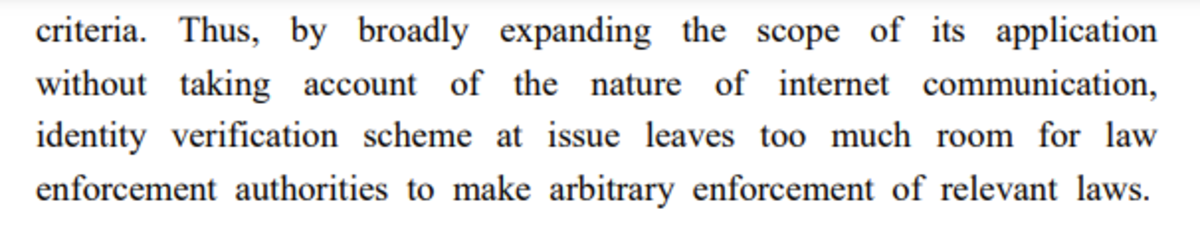

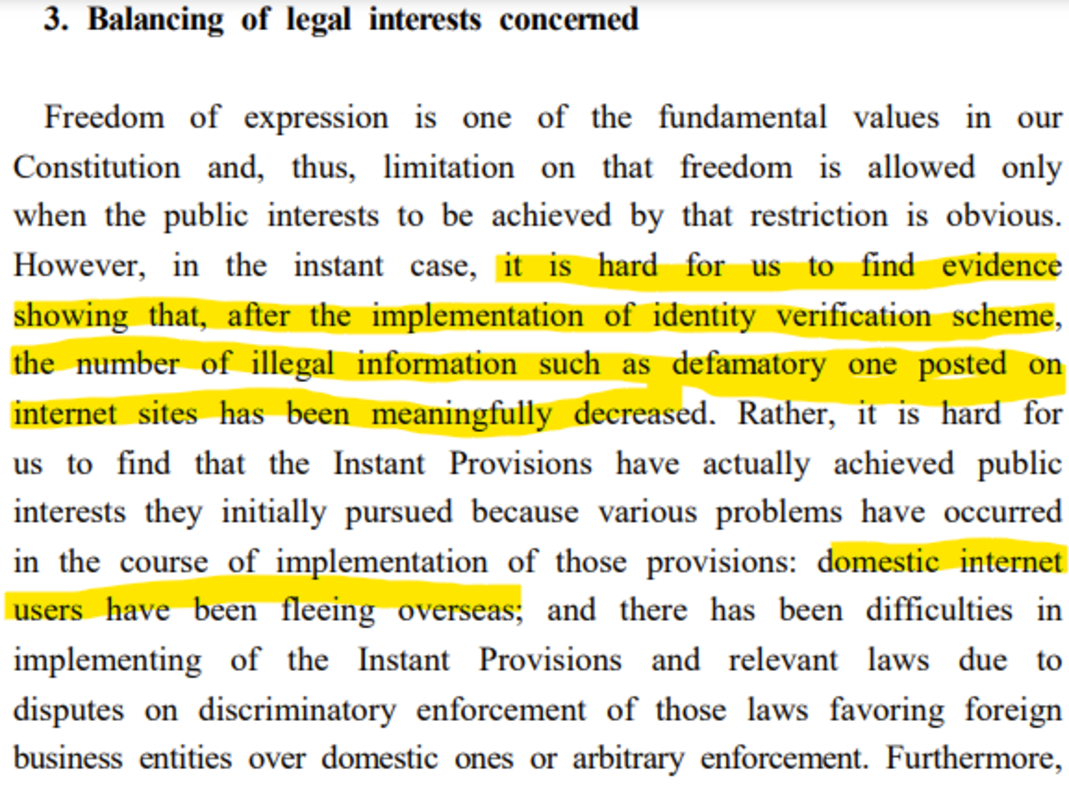

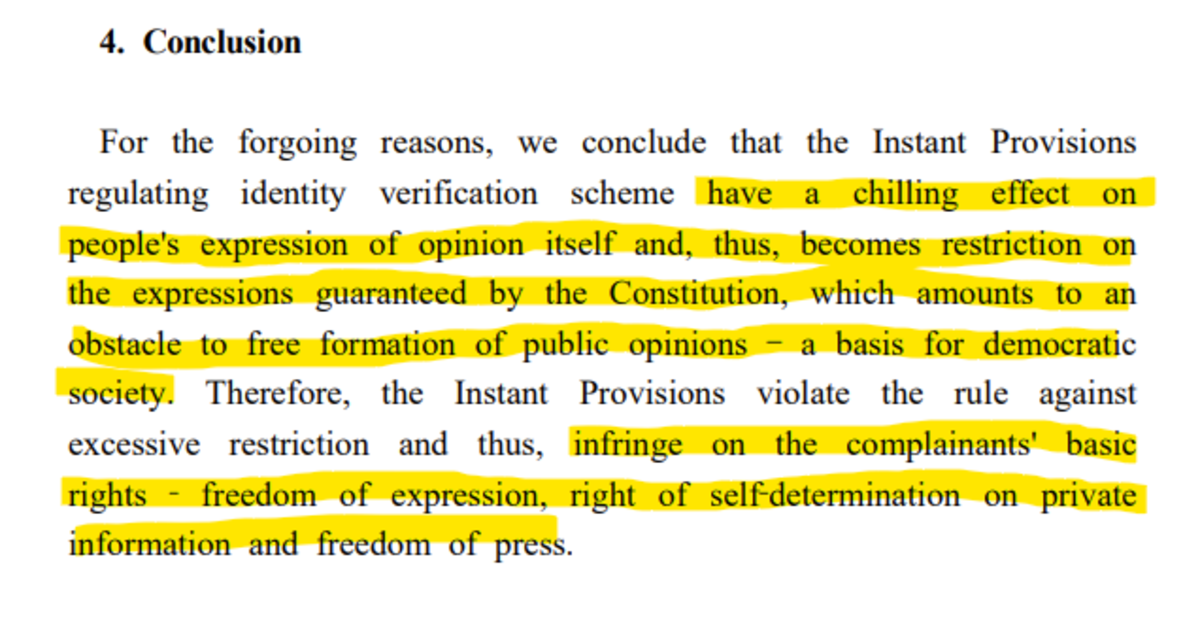

Identity collection and counter-terrorism efforts in areas outside of finance have also shown that they can be widely diverted from their original purpose. One notable example is South Korea, the first country to attempt to combat anonymity on the internet, enacting a law in 2008 requiring identity collection by social networks to combat hate speech and misinformation.

In 2012, the Constitutional Court of South Korea abolished the law45, deeming it unconstitutional. It regretfully noted numerous pitfalls: the selective and arbitrary application of this law due to its overly vague criteria, the lack of evidence showing that the law’s enforcement had reduced the quantity of illegal content posted online, and the stifling of local economic actors, who had to comply with costly standards, to the benefit of foreign actors who continued to operate in the country, attracting South Korean internet users concerned with their ability to express themselves freely.

The Court concluded by affirming that identity collection had “a chilling effect on people’s expression of opinion itself,” which constitutes “an obstacle to the free formation of public opinions — a basis for democratic society.”

One doesn’t need to go to Asia to see the danger posed by this censorship and laws aimed at combating terrorism.

In France, certain political groups, especially on the left, had a rude awakening when, after supporting various laws aimed at limiting hate speech and the glorification of terrorism, they are now targeted for “eco-terrorism” or “promotion of terrorism.” The fight against terrorism often serves as a convenient pretext to restrict the expression of legitimate political opposition, which is serious and damaging in a democracy, in which the ability to disagree with the majority opinion must absolutely be preserved.

In this regard, the parallel with the identity collection by financial institutions is striking: no evidence of their effectiveness, drastic economic standards leading to sector concentration and benefiting foreign actors, and selective enforcement by authorities of the prosecutions to be initiated, among other things.

How else can we explain, as we saw in the introduction, that developers of a Bitcoin wallet are already in pretrial detention and face up to 25 years’ imprisonment for wrongdoings attributed to them in a fallacious manner, while certain financial institutions, crypto or otherwise, regularly avoid prison sentences for much more significant and serious offenses, sometimes committed consciously?

In 2012, HSBC was accused by the US government of money laundering for Mexican drug cartels and violating sanctions against countries like Iran. The laundered amounts would approach a billion dollars46. HSBC agreed to pay a record fine of $1.9 billion to US authorities.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

Again in 2012, UBS was convicted by US authorities for assisting US citizens in evading taxes by hiding undeclared assets abroad, totaling $20 billion47. UBS paid a fine of $780 million and had to provide the names of thousands of American clients.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

Better-known in France, in 2014, BNP Paribas pleaded guilty to violating US sanctions against countries such as Sudan and Iran, as well as charges of money laundering, totaling $30 billion48. The bank agreed to pay a record fine of $8.9 billion and was temporarily banned from certain dollar transactions.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

In 2019, Danske Bank was fined €150 million by Danish authorities for facilitating large-scale money laundering, involving $227 billion49 mainly from Russia.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

In 2012, Standard Chartered was accused by US authorities of money laundering for Iranian clients, bypassing US sanctions, totaling $250 billion50. The bank agreed to pay a fine of $667 million.

But no prison sentences were imposed.

$250 billion is more than the total market capitalization of Bitcoin in 2020. That’s the magnitude we’re talking about.

The largest bank in the United States, JP Morgan, has been convicted 27751 times by the courts since 2000, for a total of nearly $40 billion in fines. That’s roughly a conviction of nearly $150 million every month for 24 years, for offenses ranging from consumer protection violations to mortgage abuses, obviously including deficiencies in anti-money laundering efforts. The latter represents $2 billion out of the $40 billion in fines.

I couldn’t find a single person in traditional finance, since the 2008 crisis, who has gone to prison on charges related to anti-money laundering or terrorism financing.

In contrast, between Pertsev, the developer of Tornado Cash, who spent nine months in prison without trial and has just been sentenced to 5 years, and the developers of Samouraï Wallet, who spent some time in prison, again without trial, and one of whom was released on bail, it seems that we are right in the midst of what the Constitutional Court of Korea called “selective enforcement by authorities of the prosecutions to be initiated.”

Not So Personal Data

The third extremely dangerous point raised by these practices of collecting customer data and combating money laundering and terrorism financing is, obviously, the theft of this data.

You don’t have to go too far back in time to find examples of data breaches exploited by cybercriminals. In France, if you’ve been unemployed even once in the past 20 years, your data is no longer personal, after a hack occurred at the National Agency for unemployment, France Travail. Your name, surname, date of birth, social security number (and therefore gender, county, and city of birth), email address, postal address, and phone number: all of this is now in the wild, in the hands of cybercriminals, who have already started using it for their deeds.

Of course, what happened to France Travail also happens in the world of finance.

Among the biggest data breaches in recent years, we can mention Equifax in 2017, an American credit rating agency, affecting the personal data of over 150 million people 52 53, or JP Morgan in 2014, with 76 million households and 7 million businesses54, or Capital One in 2019, with over 100 million affected customers, among the largest in recent years. Europe is not spared either: HSBC has experienced multiple data breaches over the past ten years55 56, but fintech companies like Revolut57 are also not immune.

In short, once your personal data is collected, the question is no longer “if” but “when” it will be accessible to hackers.

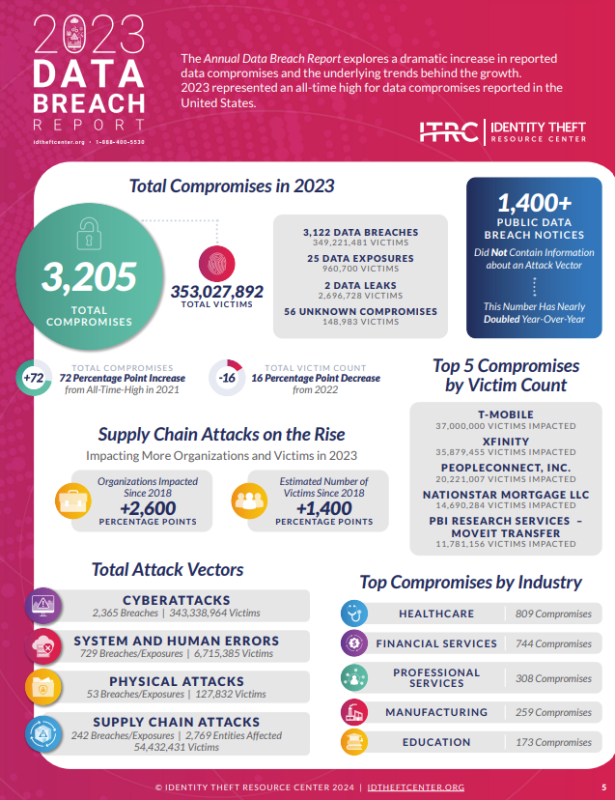

According to the Identity Theft Resource Center (ITRC), an American NGO dedicated since 1999 to evaluating identity theft crimes in the United States, there were over 3,200 data breaches or hacking events in 2023 in the United States, affecting over 350 million victims. That’s more than the entire population of the country. The financial industry emerges as the main victim, just behind the medical industry and its valuable health data58.

According to the US Federal Trade Commission, credit card frauds between 2019 and 2023 increased by over 50%, from about 280,000 consumer complaints to over 425,00059. Among these frauds, about 90% resulted from identity theft that allowed the opening of a new account in the name of a person who had their personal information stolen, and only 10% resulted from fraud on an existing card.

According to Transunion, a company that collects, monitors, and protects banking data, the use of personal data to forge new false identities reached new records in 2023, resulting in a loss of $3 billion in the United States60.

Especially with the development of AI, which reaches frightening levels of sophistication in terms of identity theft (voice, video, etc.), it becomes necessary for this “free-for-all” personal data to stop as soon as possible. Protecting personal data is therefore also a moral duty towards others because protecting oneself is protecting others from scams and breaches of trust.

It is therefore a matter of physical and digital safety for everyone. This is particularly the fight that has been launched in Switzerland, where the canton of Geneva has already voted 94% in favor of amending the constitution in favor of creating a right to digital integrity61.

Conclusion: An excessive, Unjustified, and Counterproductive Lockdown that Tramples Fundamental Rights

The practices and instruments of financial regulation impose extreme limitations on the exercise of several fundamental rights and freedoms. In particular, they disproportionately reduce both monetary confidentiality and the freedom to dispose of one’s own funds, while leading to the prohibition, legal or practical, of technologies and tools regardless of their use, as well as differences in treatment, for a given behavior, depending on the actor involved. By extension, this deals a fatal blow to innovation in Europe.

However, these practices and regulations have not been justified, as their effectiveness in combating money laundering and terrorism financing has not been “convincingly demonstrated”62, which is an obligation for the State in any endeavor to limit freedoms.

Conversely, they pose greater risks, for individuals and society, than those they claim to combat, particularly in terms of the protection of personal data (the fact that individuals cannot escape a major risk concerning very sensitive data also constitutes an infringement of their dignity).

Finally, their cost to the economy – and thus the freedom of enterprise – alone surpasses the proceeds of the crimes they claim to target.

In these circumstances, the infringements on the aforementioned fundamental rights are arbitrary and unacceptable in a democratic society.

More specifically, firstly, the rights to dignity, self-determination, and resistance to oppression are trampled upon. A substantial part of the right to property is nothing more than a chimera in a Europe where individuals must seek permission before spending their own money, without being certain that it will not be blocked the next day for a reason that has no legal basis and against which there is no effective remedy. The freedom of trade and industry is curtailed by the inability to develop innovative tools.

The right to privacy, more generally, is also violated to the point of annihilating its very essence: when anonymous cryptos are banned, and transfers without KYC are blocked, before any suspicion of wrongdoing and therefore regardless of their illicit use or not, it is privacy itself that is targeted, even though it constitutes the normal exercise of privacy.

Yet, the right to privacy protection is a pillar of democracy: described as “fundamentally fundamental” in that it “preconditions the enjoyment of most other rights and freedoms”63, it is intended “to ensure the development, without external interference, of the personality of each individual in relations with others,” to use the terms of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR)64. This capacity for personal development, associated with the freedom to make choices in complete confidentiality, guarantees the “democratic functioning of society”65.

To impose limitations on any of these fundamental freedoms, a clear and precise legal basis, motivated by a demonstrated necessity, strictly proportionate, with guarantees to attest to it is rightly expected.

But none of this is complied with as it stands. It is the advent of a presumption of guilt that paves the way for the selective application of disproportionate laws, by governments, but also by financial actors. The hypertrophy of the banking sector is indeed largely the child of these regulations, imposing staggering costs and consequently concentration, protected by giant entry barriers, leading de facto to recurring abuses of dominant position.

Preventive control of everyone, all the time, before the slightest suspicion of committing an offense, becomes the norm. Even though the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Union prohibit it. For companies subject to these regulations, the absence of control becomes an offense, in violation of primary law.

This situation should frighten any citizen desiring to live in a liberal democracy.

Thanks to Estelle De Marco, Doctor of Private Law and Criminal Sciences, expert with the Council of Europe specializing in the protection of fundamental rights, for her contribution on legal developments.

[36] World Bank Group, What Does Digital Money Mean for Emerging Market and Developing Economies?, 2022, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099736004212241389/pdf/P17300602cf6160aa094db0c3b4f5b072fc.pdf

[37] Anti-Money Laundering Regulation EU, 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0365_EN.pdf

[38] Cour EDH, Podchasov v. Russia, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/?i=001-230854.

[39] Does crime still pay? Criminal Asset Recovery in the EU, Survey of Statistical Information 2010–2014, 2016, https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/criminal_asset_recovery_in_the_eu_web_version.pdf

[40] Voir les références dans le papier de Ronald Pol.

[41] Paul Vieira, Canada’s Use of Emergency Powers to End Trucker Protests Was Unconstitutional, Judge Rules, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/americas/canadas-use-of-emergency-powers-to-end-trucker-protests-was-unconstitutional-judge-rules-6a537434

[42] https://twitter.com/Nigel_Farage/status/1674357026921623552

[43] Ben Quinn, Jim Waterson, BBC writes to Farage to apologise over Coutts bank account report, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/jul/24/bbc-writes-to-farage-to-apologise-over-coutts-bank-account-report

[44] https://twitter.com/DavidDavisMP/status/1681656257600532481

[45] Human Rights Foundation, The Financial Freedom Report #17, 2024, https://mailchi.mp/hrf.org/hrfs-weekly-financial-freedom-report-290691

[46] https://twitter.com/incindia/status/1770707793730838967?mc_eid=332f07f5f9

[47] Main Modi opponent Kejriwal challenges arrest ahead of India election, 2024, https://www.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20240322-modi-s-main-opponent-kejriwal-held-in-graft-probe-ahead-of-indian-elections

[48] https://english.ccourt.go.kr/ “Identity Verification System on Internet”, 23 Août 2012

[49] Marc L. Ross, HSBC’s Money Laundering Scandal, 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/stock-analysis/2013/investing-news-for-jan-29-hsbcs-money-laundering-scandal-hbc-scbff-ing-cs-rbs0129.aspx#:~:text=HSBC%20Bank%20USA%20laundered%20%24881,to%20result%20from%20systematic%20failures.

[50] Trial Begins for Ex-UBS Banker Accused of Hiding $20 Billion in US Assets, 2014, https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/2675-trial-begins-for-ex-ubs-banker-accused-of-hiding-20-billion-in-us-assets

[51] BNP Paribas accepte de payer une amende record aux Etats-Unis, 2014, https://www.leparisien.fr/economie/bnp-paribas-le-montant-de-l-amende-fixe-ce-lundi-soir-30-06-2014-3964657.php

[52] Teis Jensen, Danske Bank’s 200 billion euro money laundering scandal, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1NO10D/

[53] Dominic Rushe, Jill Treanor, Standard Chartered bank accused of scheming with Iran to hide transactions, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2012/aug/06/standard-chartered-iran-transactions#:~:text=Standard%20Chartered%20bank%20ran%20a,of%20the%20UK%2Dbased%20bank.

[54] Violation Tracker, Parent Company JP Morgan Chase https://violationtracker.goodjobsfirst.org/?parent=jpmorgan-chase

[55] Todd Haselton, Credit reporting firm Equifax says data breach could potentially affect 143 million US consumers, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/07/credit-reporting-firm-equifax-says-cybersecurity-incident-could-potentially-affect-143-million-us-consumers.html

[56] FCA, Final Notice to Equifax Unlimited, 2023, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/final-notices/equifax-limited-2023.pdf

[57] Tara Siegel Bernard, Ways to Protect Yourself After the JPMorgan Hacking, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/04/your-money/jpmorgan-chase-hack-ways-to-protect-yourself.html

[58] Scott Ferguson, HSBC Data Breach Shows Failure to Protect Passwords & Access Controls, 2018, https://www.darkreading.com/cyber-risk/hsbc-data-breach-shows-failure-to-protect-passwords-access-controls

[59] Elise Viebeck, HSBC Finance alerts customers to data breach, 2015, https://thehill.com/policy/cybersecurity/239408-hsbc-finance-alerts-customers-to-data-breach/

[60] Carly Page, Revolut confirms cyberattack exposed personal data of tens of thousands of users, 2022 https://techcrunch.com/2022/09/20/revolut-cyb erattack-thousands-exposed/

[61] 2023 Data Breach Report, Identity Theft Resource Center, 2024, https://www.idtheftcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/ITRC_2023-Annual-Data-Breach-Report.pdf

[62] Federal Trade Commission, Identity Theft Reports, 25 avril 2024 (données du 31 mars 2024), https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/federal.trade.commission/viz/IdentityTheftReports/TheftTypesOverTime

[63] TransUnion, TransUnion Analysis Finds Synthetic Identity Fraud Growing to Record Levels, 24 août 2023, https://newsroom.transunion.com/transunion-analysis-finds-synthetic-identity-fraud-growing-to-record-levels/

[64] Yannick Chavanne, Genève fait figure de pionnier en introduisant l’intégrité numérique dans sa Constitution, 2023, https://www.ictjournal.ch/news/2023-06-19/geneve-fait-figure-de-pionnier-en-introduisant-lintegrite-numerique-dans-sa

[65] Cour EDH, ch., 25 février 1993, Crémieux c. France, req. n°11471/85, § 38, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre?i=001-62362.

[66] Antoinette Rouvroy et Yves Poullet, ‘The right to Informational Self-Determination and the Value of Self-Development: Reassessing the Importance of Privacy for Democracy’, in Serge Gutwirth et al., Reinventing Data Protection?, janvier 2009, p. 45–76, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225248944_The_Right_to_Informational_Self-Determination_and_the_Value_of_Self-Development_Reassessing_the_Importance_of_Privacy_for_Democracy , p. 16. See also Fabrice Rochelandet, ‘II. Quelles justifications à la vie privée ?’, in Économie des données personnelles et de la vie privée (2010), p. 21–37, https://www.cairn.info/Economie-des-donnees-personnelles-et-de-la-vie-pri–9782707157652-page-21.htm?contenu=resume. Voir aussi Antoine Buyse, ‘The Role of Human Dignity in ECHR Case-Law’, 21 octobre 2016, https://www.echrblog.com/2016/10/the-role-of-human-dignity-in-echr-case.html .

[67] CEDH, Botta v. Italie, 1998, §32, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-62701.

[68] Antoinette Rouvroy et Yves Poullet, précités, p. 13.

This is a guest post by Alexandre Stachtchenko. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Recent Posts

Categories

Related Articles

President Trump Has Got A Bold Vision For Bitcoin In America

As President Donald Trump’s second term begins, the Bitcoin community looks to...

ByglobalreutersJanuary 17, 2025Wyoming Introduces Bitcoin Strategic Reserve Bill

A look at a bill being proposed for a Wyoming state level...

ByglobalreutersJanuary 17, 2025Treat Bitcoin As A Tool, Not A Cult

Ignore the mindless chanting of slogans, and do what you want with...

ByglobalreutersJanuary 17, 2025How the Updated MVRV Z-Score Improves Bitcoin Price Predictions

We’ve enhanced the MVRV Z-Score to better reflect Bitcoin’s evolving market dynamics...

ByglobalreutersJanuary 17, 2025

Leave a comment