- Home

- Features

- Business

- Active

- Sports

- Shop

Top Insights

Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman passed away today. His work incorporating psychology into economics through Prospect Theory has been a major advance. From the N.Y. Times obituary:

Professor Kahneman delighted in pointing out and explaining what he called universal brain “kinks.” The most important of these, the behaviorists hold, is loss-aversion: Why, for example, does the loss of $100 hurt about twice as much as the gaining of $100 brings pleasure?

Among its myriad implications, loss-aversion theory suggests that it is foolish to check one’s stock portfolio frequently, since the predominance of pain experienced in the stock market will most likely lead to excessive and possibly self-defeating caution.

Loss-aversion also explains why golfers have been found to putt better when going for par on a given hole than for a stroke-gaining birdie. They try harder on a par putt because they dearly want to avoid a bogey, or a loss of a stroke.

For a good introduction of Kahneman’s contribution, one can read the book Thinking, Fast and Slow. More technically, Prospect Theory helped to solve some of the key paradoxes in expected utility theory. From the Nobel Prize website:

Departures from the von Neumann-Morgenstern-Savage expected-utility theories of decisions under uncertainty were first pointed out by the 1988 economics laureate Maurice Allais (1953a), who established the so-called Allais paradox (see also Ellsberg, 1961, for a related paradox). For example, many individuals prefer a certain gain of 3,000 dollars to a lottery giving 4,000 dollars with 80% probability and 0 otherwise. However, some of these same individuals also prefer winning 4,000 dollars with 20% probability to winning 3,000 dollars with 25% probability, even though the probabilities for the gains were scaled down by the same factor, 0.25, in both alternatives (from 80% to 20%, and from 100% to 25%). Such preferences violate the so-called substitution axiom of expected-utility theory…

One striking finding is that people are often much more sensitive to the way an outcome differs from some non-constant reference level (such as the status quo) than to the outcome measured in absolute terms. This focus on changes rather than levels may be related to well-established psychophysical laws of cognition, whereby humans are more sensitive to changes than to levels of outside conditions, such as temperature or light.

Moreover, people appear to be more adverse to losses, relative to their reference level, than attracted by gains of the same size.

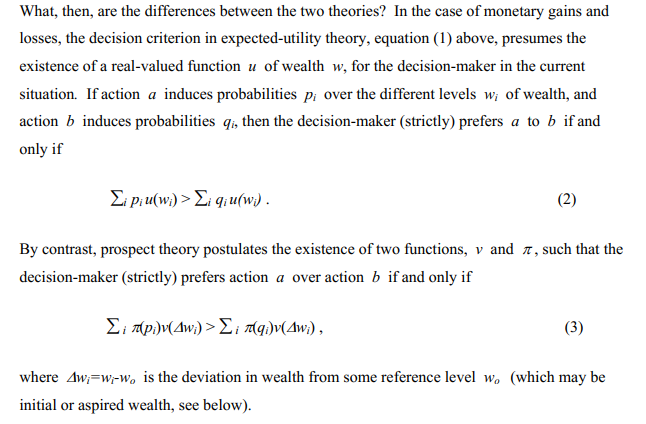

And some of the mathematics behind prospect theory:

The key differences between expected utility and prospect theory: (i) expected utility cares about levels whereas prospect theory evaluates changes against status quo [i.e., w vs. Δw], (ii) prospect theory allows the utility function and risk preferences to for gains relative to losses [i.e., u(w) vs. v(w)] ], and (iii) expected utility theory takes probabilities as given whereas prospect theory uses decision weights which account for how individuals perceive these probabilities [i.e., p vs. π(p)].

While Prospect Theory likely represents real-world human decision-making processes more accurately than expected utility theory, some criticisms of Prospect Theory would be that (i) with repeated games, individuals often revert to closer to an expected utility framework and (ii) for researchers, identifying a ‘status quo’ value for each individual is often challenging in practice.

Nevertheless, the Nobel Prize was much deserved and the scientific contributions Kahneman (and his collaborator Amos Tversky) will live on for posterity.

Recent Posts

Categories

Related Articles

Carlyle and SK Capital Partners are buying beleaguered gene therapy biotech Bluebird...

ByglobalreutersFebruary 21, 2025Hospitals are adopting AI technology more than ever before, but they still...

ByglobalreutersFebruary 21, 2025This fact sheet provides an overview of the history of the Kemp-Kasten...

ByglobalreutersFebruary 21, 2025

Leave a comment